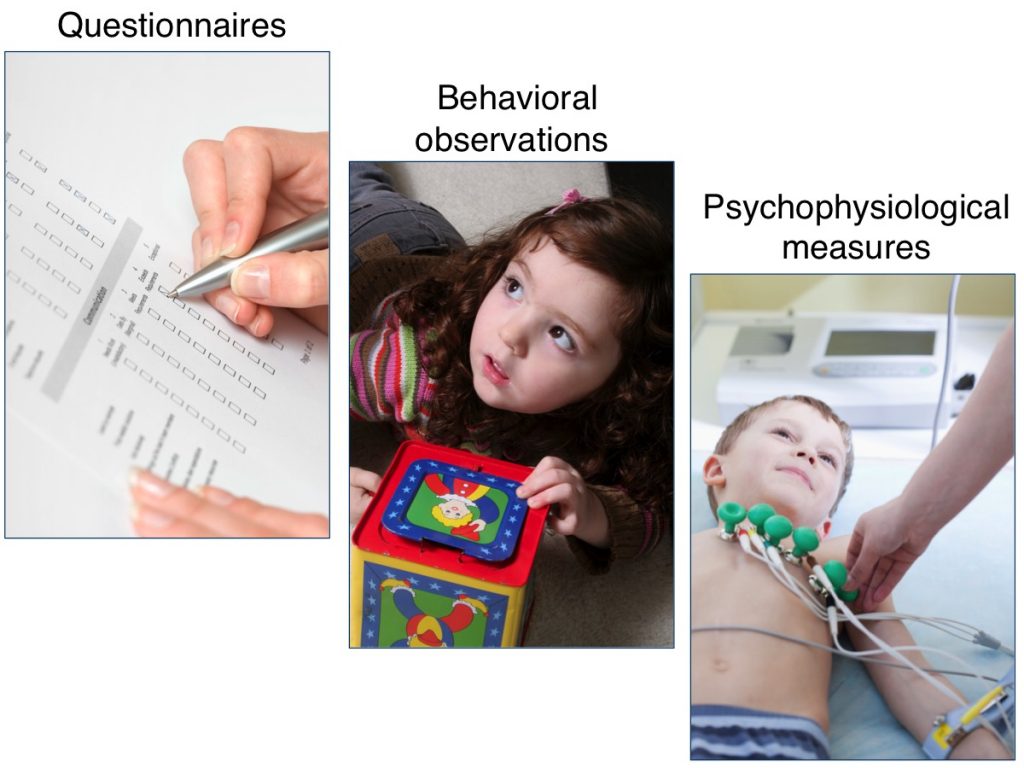

There are different ways to study temperament. We can ask questions about behavior, observe behavior, or use psychophysiological measures.

Some researchers use questionnaires. Parents or teachers answer questions about a child’s behavior across different situations and ages. One widely used parent-report measure is the Infant Behavior Questionnaire Revised. Parents rate how often their infant shows different behaviors such as vocalizations and fear. They answer questions like “How often during the last week did the baby startle to a sudden or loud noise?”

Researchers also observe children’s behaviors in situations designed to show their temperament. For instance, they might give a child a toy that makes an unexpected noise and look at how the child responds. Does the child show mild fear? Or is she unfazed by the noise?

A child’s psychophysiological measures teach us about the connections between biology and behavior. These measures include heart rate, hormone levels, and brain activity. For instance, resting heart rate tends to be higher in timid children.

There are advantages and disadvantages to using each measure. So, researchers often use more than one measure in their studies. Together, these measures can give us a rich picture of a child’s temperament.

-

- Anterior cingulate cortex

- part of the brain that helps control emotional impulses

- Dimension

- more or less of a behavior

- Goodness of fit

- occurs when your expectations are compatible with a child’s temperament

- Negative reactivity

- a tendency to react in a negative manner

- Positive reactivity

- a tendency to react in a positive manner

- Prefrontal cortex

- the decision-making area of the brain

- Self-regulation

- a child’s ability to concentrate, to manage emotions, and to control impulses

- Temperament

- how a person approaches the world